Difference between revisions of "City of Little Rock"

(→Demographics) |

(→Little Rock as State Capitol) |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Skyline-little-rock.jpg|thumb|300px|Little Rock Skyline from North Little Rock. Photo by Phil Frana.]] |

| − | + | [[Image:City-of-little-rock.JPG|thumb|300px|Skyline of Little Rock at night. Photo courtesy of Spencer Smith.]] | |

| − | [[Image:City-of-little-rock.JPG|thumb|Skyline of Little Rock at night. Photo courtesy of Spencer Smith.]] | + | The '''City of Little Rock''' is an incorporated municipality in [[Pulaski County]], Arkansas. The city is the political and commercial center of the state. |

| − | The '''City of Little Rock''' is | ||

| − | [[Little Rock City Hall]] is located at 500 West Markham Street. | + | City government is divided into a number of city departments, citizen services offices, commissions, bureaus, and task forces. Little Rock is led by the [[Little Rock Mayor's Office|Mayor's Office]], the [[Little Rock City Manager's Office|City Manager's Office]], and the [[Little Rock Board of Directors|Board of Directors]]. Services provided by the City of Little Rock are funded by a series of bonds, and accomplished by approximately 2,500 employees. The city has an extensive municipal code. [[Little Rock City Hall|City Hall]] is located at 500 West Markham Street. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Geology and Climate== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Little Rock is located on the western edge of the alluvial plains of the Arkansas Delta where the [[Ouachita Mountains]] end. The city sits on an elevated bluff on the southern side of the [[Arkansas River]], which generally protected it from flooding in its early history. The city sits at an elevation of about 257 feet above sea level. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The average maximum temperature in January is 51 degrees. The average minimum in January is 31. In April the average maximum is 74 degrees. The average minimum temperature is 51. In July the average maximum temperature is 93 degrees. The average minimum temperature is 71. In October the average maximum temperature is 76 degrees. The average minimum temperature is 50. Average snowfall varies from a trace in March, April, and November, to one inch in December, three inches in January, and two inches in February. Precipitation averages range from three inches in the summer months to five inches in winter and spring. The average date of the first freeze is November 15th. The average date of the last freeze in the spring is March 16th. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==City government== | ||

====Departments==== | ====Departments==== | ||

| − | [[Image:City-hall-corner.jpg|thumb|The City of Little Rock operates out of City Hall. The building once had a dome. Photo by Phil Frana.]] | + | [[Image:City-hall-corner.jpg|thumb|300px|The City of Little Rock operates out of City Hall. The building once had a dome. Photo by Phil Frana.]] |

The City of Little Rock has fourteen departments dedicated to four areas of service: public safety, infrastructure, economic development, and quality of life. | The City of Little Rock has fourteen departments dedicated to four areas of service: public safety, infrastructure, economic development, and quality of life. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 21: | ||

*[[District Courts]] | *[[District Courts]] | ||

*[[Finance]] | *[[Finance]] | ||

| − | *[[Fire]] | + | *[[Little Rock Fire Department|Fire]] |

*[[Fleet Service]] | *[[Fleet Service]] | ||

*[[Housing and Neighborhood Programs]] | *[[Housing and Neighborhood Programs]] | ||

| Line 20: | Line 27: | ||

*[[Information Technology]] | *[[Information Technology]] | ||

*[[Parks and Recreation]] | *[[Parks and Recreation]] | ||

| − | *[[Planning and Development]] | + | *[[Little Rock Planning and Development Department|Planning and Development]] |

*[[Police]] | *[[Police]] | ||

*[[Public Works]] | *[[Public Works]] | ||

| − | *[[Zoo]] | + | *[[Little Rock Zoo|Zoo]] |

====Commissions, Bureaus, Task Forces==== | ====Commissions, Bureaus, Task Forces==== | ||

| Line 52: | Line 59: | ||

*[[Oakland Fraternal Cemetery Board]] | *[[Oakland Fraternal Cemetery Board]] | ||

*[[Parks and Recreation Commission]] | *[[Parks and Recreation Commission]] | ||

| − | *[[Little Rock Port Authority]] | + | *[[Little Rock Port Authority|Port Authority]] |

*[[Project Progress Committee]] | *[[Project Progress Committee]] | ||

*[[Racial and Cultural Diversity Commission]] | *[[Racial and Cultural Diversity Commission]] | ||

| Line 63: | Line 70: | ||

*[[Little Rock Mayor's Office]] | *[[Little Rock Mayor's Office]] | ||

| − | *[[Little Rock Vice Mayor's Office]] | + | *[[Little Rock Vice Mayor|Little Rock Vice Mayor's Office]] |

*[[Little Rock City Manager's Office]] | *[[Little Rock City Manager's Office]] | ||

*[[Little Rock Board of Directors]] | *[[Little Rock Board of Directors]] | ||

*[[Little Rock City Clerk's Office]] | *[[Little Rock City Clerk's Office]] | ||

| − | == | + | ==Demographics, Economics, Transportation== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Demographics==== | ====Demographics==== | ||

| − | Little Rock is the capitol city of the | + | Little Rock is the capitol city of the [[State of Arkansas]]. The city encompasses 122 square miles of incorporated land. In 2003 the U.S. Census Bureau estimated population of the city was 184,053, with 55.1% Caucasian, 40.4% African American, and 2.7% Hispanic. More than half a million people live in the Greater Little Rock Metropolitan area. |

''Population:'' | ''Population:'' | ||

| Line 129: | Line 106: | ||

*2007 - 193,275 (est.) | *2007 - 193,275 (est.) | ||

| − | ==== | + | ====Economy==== |

| + | |||

| + | ====Transportation==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The city is known for six important downtown bridges over the Arkansas River connecting the city to [[North Little Rock]] and northern Pulaski County. The six bridges are the [[Baring Cross Bridge]], [[Broadway Bridge]], [[Main Street Bridge]], [[Junction Bridge]], [[I-30 Bridge]], and the [[Rock Island Bridge]]. Other bridges in the city that connect the north and south banks of the river are the [[I-430 Bridge]], the pedestrian-only [[Big Dam Bridge]], and the [[I-440 Bridge]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The city lies at the intersection of two major interstates, [[I-30]] and [[I-40]]. East-west crosstown traffic is facilitated by [[I-630]]. The city is ringed on the west by [[I-430]] and on the east by [[I-440]]. [[Interstate 530]] connects the city to Pine Bluff to the south. Two other limited access highways are [[U.S. Highway 67]], connecting Little Rock to [[Jacksonville]] to the northeast, and [[Arkansas Highway 100]], connecting the city to [[Maumelle]] to the northwest. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Arkansas Highway 10]] in the city is known as [[Cantrell Road]]. [[Arkansas Highway 5]] follows [[Stagecoach Road]] and [[Colonel Glenn Road]]. [[U.S. Highway 67]] and [[U.S. Highway 70]] are merged with I-30 on the southwest and northern sides of the city, both following [[University Avenue]], [[Asher Avenue]], [[Roosevelt Road]], and [[Broadway]] downtown. [[Arkansas Highway 300]] follows Colonel Glenn Road into western Pulaski County. Access to the city from [[Sweet Home]] and the southeast is possible on [[Arkansas Highway 365]]. In southwestern Little Rock [[Arkansas Highway 338]] is known as [[Baseline Road]]. [[Arkansas Highway 367]] is known as [[Pike Street]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Little Rock is served by several railroads. The [[Union Pacific Railroad]] enters downtown by way of two separate lines entering the city from the northeast, northwest, southeast, and southwest. [[Amtrak]] uses the northeast-to-southwest line for passenger traffic, stopping at [[Union Station]] near the [[Arkansas State Capitol]]. The [[Little Rock and Western Railway]] follows the Arkansas River downtown from the direction of [[Bigelow]] in [[Perry County]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Passenger travel is also facilitated by the [[Little Rock National Airport]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==History of Little Rock== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Human prehistory==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Woodland period [[Plum Bayou]] people settled in this part of the Arkansas River valley around 650 AD. The original name of the inhabitants is unknown; the name Plum Bayou is derived from a nearby creek. Remains from this culture are still visible at the [[Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park]] sixteen miles southeast of the city near [[Scott]]. The Plum Bayou culture occupied the Toltec Mounds site until 1050 AD, when they were abandoned. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Quapaw]] (Ugahxpa, or "Downstream People") are a Native American tribe that may have migrated from the Ohio River Valley to the Lower Mississippi and Arkansas River valleys before the time of European settlement. Other native peoples referred to the Quapaw as the "Akansea," from which the name of the state of Arkansas is derived. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====European discovery and exploration==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The site of the present city of Little Rock was first visited by European explorers in 1722, when Frenchman [[Jean-Baptise Bénard de la Harpe]] made note of [[La Petite Roche]] ("the little rock"). The first squatter on Little Rock land may have been [[William Lewis]], who built a shelter at the present location of the [[Old State House]] in 1812. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====A Crossroads Settlement==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | On August 24, 1818, the Quapaw Indians ceded all their lands west of present Rock Street in [[Little Rock]] to the United States in preparation for a move of the seat of government to the city from Arkansas Post near the mouth of the Arkansas River. The loss of land amounted to 16 million acres in southern and western Arkansas, including almost all land held between the Arkansas and Red rivers. That same year [[Pulaski County]] became part of the Missouri Territory. The city gained a post office on April 10, 1820, with the appointment of postmaster [[Amos Wheeler]], and became the territorial capitol on October 24, 1820. Little Rock was surveyed in 1821, and briefly became known as "Arkopolis." The first Little Rock school opened under [[Jesse Brown]] in 1823. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On November 15, 1824, the Quapaw tribe ceded the remainder of their lands east of Rock Street, an amount totaling 1.5 million acres. A [[Quapaw Line]] monument dedicated to the memory of these two treaties stands today on the southeast corner of Commerce and Ninth streets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Little Rock as State Capitol==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Arkansas legislature]] incorporated incorporated Little Rock as a town on November 7, 1831, and as a city on November 2, 1835. It became the state capitol in 1836. The first steam ferry across the Arkansas River began operations on June 27, 1839, and the first hotel - [[Anthony House]] - opened in 1841. By 1850 the city, expanding rapidly during the cotton boom, held about 2,000 denizens. The population grew to 3,727 in 1860. By 1870 the number of residents had tripled to 12,380. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Civil War Little Rock==== | ||

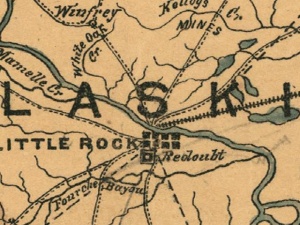

| + | [[Image:White-oak-bayou.JPG|thumb|300px|Little Rock on c. 1864 Map of Arkansas & Louisiana by Helmuth Holtz.]] | ||

| + | During the [[American Civil War]] the city observed much military activity. On February 8, 1861, the Federal [[Little Rock Arsenal]] was attacked by Confederate forces and its store of ammunition, cannon, and other weapons seized. Under the leadership of Major General [[Samuel R. Curtis]] 22,000 Union soldiers feigned an attack on Little Rock in May 1862, causing the state to establish a government in exile in Jackson, Mississippi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The city was captured in September 1863 by fourteen thousand federal troops under the command of Major General [[Frederick Steele]]. C.S.A. Major General [[Sterling Price]] attempted to defend the city with eight thousand men and miscellaneous cavalry. Steele bypassed this installations by crossing the Arkansas River on a pontoon bridge erected at [[Terry's Ferry]]. Confederate cavalrymen under the leadership of Brigadier General [[John Sappington Marmaduke]] met Union cavalry under Brigadier General [[John W. Davidson]] at [[Fourche Bayou]] east of the city (site of the present [[Port of Little Rock]]). The Confederate stand at Fourche Bayou gave Price time to evacuate all of his troops before the city surrendered for the duration of the war. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====A City of Roses==== | ||

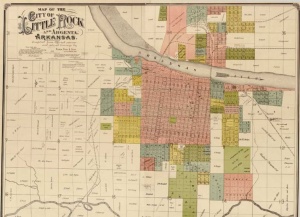

| + | [[Image:1888-little-rock-map.jpg|thumb|300px|Little Rock and Argenta with additions, extensions, and subdivisions in 1888.]] | ||

| + | At the turn of the century Little Rock was called the "City of Roses," for its long tradition of civic gardening. In 1914 the [[Arkansas State Capitol]] was completed in midtown Little Rock, precipitating a building boom that culminated with the completion of the fourteen-story [[Donaghey Building]] in 1926. Downtown retail development, spurred by flagship stores [[Blass Department Store]] and [[M. M. Cohn]], grew until 1957 when the first suburban shopping center ([[Village Shopping Center]]) opened its doors at the corner of Asher & University. | ||

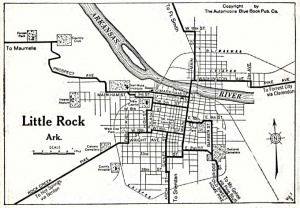

| + | [[Image:Little-rock-map-1920.jpg|thumb|300px|Little Rock street system in 1920.]] | ||

| + | ====The Great Depression==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The Second World War==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The Crisis of 1957==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Little Rock had long been controlled by the mayor-alderman form of government. On November 11, 1957, voters turned control over to a city manager. Local historian James Bell has suggested that the change was made in part because of the turmoil roiling the city during the [[Little Rock Crisis]]: "Possibly because of state intervention in the Little Rock school crisis, which in turn caused Federal intervention, the city's voters favored a stronger municipal government." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Revitalization Efforts==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The City of Little Rock has taken a number of steps since the 1960s to restore downtown to its former position of prominence and hospitality. The city has focused on some of the same goals driving other revitalizing cities like [[Portland]], San Antonio, and Baltimore. These goals include improving the quality and number of downtown entertainment venues and attractions, adding green space buffers, beautiful streetscapes, and waterfront attractions, improving walkability and transportation options, creating safe living spaces for a twenty-four hour resident population, revisiting zoning laws, and not least of all forging significant public-private partnerships and cooperative ventures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A number of government and public-private partnerships have been formed over the years to accomplish these aims, most notably the [[Little Rock Housing Authority]] (1937), [[Urban Progress Association]] (1959), [[Downtown Little Rock Unlimited]] (1959), [[Little Rock Unlimited Progress]] (1970), the [[Metrocentre Improvement District]] (1973), and the [[Little Rock Downtown Partnership]] (1985). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Redirecting attention back downtown has not been easy. In an attempt to recapture some of the trade draining into the western suburbs the group [[Little Rock Unlimited Progress]] inaugurated the ill-fated $4.5 million [[Metrocentre Mall]] which replaced Main Street from Third Street to Seventh Street with a brick-lined pedestrian mall in 1975. More successfully in 1982 the [[Statehouse Convention Center]] opened near the corner of Main and Markham next to the new [[Excelsior Hotel]]. The shuttered [[Capital Hotel]] reopened after $10 million in renovations the very next year. Also in 1983 the [[Little Rock Department of Parks and Recreation]] opened the $2 million [[Riverfront Park]], an idea on the drawing board since 1914, and kicked off the inaugural Memorial Day weekend event known as [[Riverfest]]. By 1988 the city hosted 600 conventions and 220,000 visitors due in no small part to the efforts of downtown city leaders. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The apparent success of Metrocentre Mall encouraged investors to sink $13 million into city revenue bonds to fund the [[Main Street Market project]], which brought an enclosed shopping center to the downtown district in 1987. Five buildings were connected along Capitol and Main streets to form an indoor mall. The oldest escalators in the state, once owned by JCPenney, were refurbished as well as 177,000 square feet of office, restaurant, and retail space. Main Street Market was connected to the [[Arkansas Repertory Theatre]] and a parking deck by skywalks. Within four years, however, the Market failed as a retailing and entertainment destination. Today it is exclusively used as office space. Metrocentre Mall failed as well. Main reopened to vehicular traffic around 1995. [[Barry Travis]], former executive director of the Little Rock Convention and Visitors Bureau, has blamed a lack of free parking as a major reason for the decline of both revitalization efforts. The 1994 HBO documentary [[Gang War: Bangin' in Little Rock]] also reinforced the public imagination of downtown as an unsafe destination. Much of the east side was composed of aging or derelict warehouses. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A "critical mass" may only have been reached in 1996 when [[Ottenheimer Market Hall]] reopened in the [[River Market District]] to great fanfare. The Market Hall almost immediately helped renew retail opportunities and bring nightlife back into the city center. By 2001 the city was hosting 700 conventions and 300,000 visitors who spent an estimated $100 million. A five-year effort to site the [[William J. Clinton Presidential Center]] in the city was capped by the 2004 dedication of the Clinton Library, bringing an estimated $1 billion in additional investment into the historic [[River Market District]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Little Rock Today==== | ||

''Attractions:'' | ''Attractions:'' | ||

| Line 176: | Line 219: | ||

*[[Quapaw Quarter Association]] | *[[Quapaw Quarter Association]] | ||

| − | '' | + | ''Public Services:'' |

*[[Little Rock Convention and Visitors Bureau]] | *[[Little Rock Convention and Visitors Bureau]] | ||

| Line 201: | Line 244: | ||

*[[Stephens Inc.]] | *[[Stephens Inc.]] | ||

*[[Stone Ward]] | *[[Stone Ward]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | *David W. Baird, ''The Quapaw Indians: A History of the Downstream People,'' (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980). | ||

| + | *S. Charles Bolton, "Under Three Flags," in ''A Documentary History of Arkansas,'' eds. C. Fred Williams, et al. (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1984), p. 3-5. | ||

| + | *Isaac Joslin Cox, ed., ''The Journeys of René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle,'' vol. 1 (New York: Allerton Book Company, 1922). | ||

*Jay Harrod and Kerry Kraus, "Capital Improvements: A Look at Little Rock's Past and Future Downtown Revitalization Efforts," Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism, April 9, 2002, unpublished. | *Jay Harrod and Kerry Kraus, "Capital Improvements: A Look at Little Rock's Past and Future Downtown Revitalization Efforts," Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism, April 9, 2002, unpublished. | ||

*Letha Mills and H. K. Stewart, ''Greater Little Rock: A Contemporary Portrait'' (Chatsworth, CA: Windsor Publications, 1990). | *Letha Mills and H. K. Stewart, ''Greater Little Rock: A Contemporary Portrait'' (Chatsworth, CA: Windsor Publications, 1990). | ||

| + | *Susan Nichols, ''Knapp Trail Guide'' brochure. | ||

| + | *Milton D. Rafferty and John C. Catau, ''The Ouachita Mountains: A Guide for Fishermen, Hunters, and Travelers'' (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 10. | ||

| + | *John Hugh Reynolds, ed., "Marquette's Reception by the Quapaws, 1673," ''Publications of the Arkansas Historical Association'' 1 (1906): 500-502. | ||

| + | *George B. Rose, "Little Rock: The City of Roses," in ''Historic Towns of the Southern States,'' ed. Lyman Pierson Powell (G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1904), 537-556. | ||

| + | *Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park, ''The Griggs Canoe'' brochure. | ||

| + | *Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park, ''Plum Bayou Trail'' brochure. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | *[http://www.cast.uark.edu/parkin/ Ancient Monuments in Arkansas] | ||

*[http://www.littlerock.org/ Homepage of the City of Little Rock] | *[http://www.littlerock.org/ Homepage of the City of Little Rock] | ||

| + | *[http://www.littlerock.org/Images/UserFiles/PDF/StatisticsReports/1-22.pdf MacArthur Park Historic District: Guidelines for Rehabilitation and New Construction] | ||

| + | *[http://www.arkansasstateparks.com/toltecmounds/ Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park] | ||

| + | *[http://www.aetn.org/programs/exploringarkansas/archives/archives/toltec_mounds_archeological_state_park Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park - AETN Exploring Arkansas] | ||

| + | *[http://www.uark.edu/campus-resources/archinfo/toltec.html Toltec Mounds Research Station] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Cities]] |

Latest revision as of 20:38, 28 April 2010

The City of Little Rock is an incorporated municipality in Pulaski County, Arkansas. The city is the political and commercial center of the state.

City government is divided into a number of city departments, citizen services offices, commissions, bureaus, and task forces. Little Rock is led by the Mayor's Office, the City Manager's Office, and the Board of Directors. Services provided by the City of Little Rock are funded by a series of bonds, and accomplished by approximately 2,500 employees. The city has an extensive municipal code. City Hall is located at 500 West Markham Street.

Contents

Geology and Climate

Little Rock is located on the western edge of the alluvial plains of the Arkansas Delta where the Ouachita Mountains end. The city sits on an elevated bluff on the southern side of the Arkansas River, which generally protected it from flooding in its early history. The city sits at an elevation of about 257 feet above sea level.

The average maximum temperature in January is 51 degrees. The average minimum in January is 31. In April the average maximum is 74 degrees. The average minimum temperature is 51. In July the average maximum temperature is 93 degrees. The average minimum temperature is 71. In October the average maximum temperature is 76 degrees. The average minimum temperature is 50. Average snowfall varies from a trace in March, April, and November, to one inch in December, three inches in January, and two inches in February. Precipitation averages range from three inches in the summer months to five inches in winter and spring. The average date of the first freeze is November 15th. The average date of the last freeze in the spring is March 16th.

City government

Departments

The City of Little Rock has fourteen departments dedicated to four areas of service: public safety, infrastructure, economic development, and quality of life.

- City Attorney's Office

- Community Programs

- District Courts

- Finance

- Fire

- Fleet Service

- Housing and Neighborhood Programs

- Human Resources

- Information Technology

- Parks and Recreation

- Planning and Development

- Police

- Public Works

- Zoo

Commissions, Bureaus, Task Forces

- Advertising and Promotion Commission

- Airport Commission

- Ambulance Authority

- Americans with Disabilities Act Citizen's Grievance Committee

- Animal Services Advisory Board

- Arkansas Arts Center Board of Trustees

- Arkansas Museum of Discovery Board of Trustees

- Arts and Culture Commission

- Board of Adjustment

- Central Arkansas Library System Board of Trustees (CALS)

- Central Arkansas Transit Authority Board of Directors (CATA)

- Central Arkansas Water Commission

- Children, Youth, and Families Commission

- City Beautiful Commission

- Civil Service Commission

- Community Housing Advisory Board

- Construction Board of Adjustment and Appeals

- Historic District Commission

- Housing Authority Board of Commissioners

- Housing Board of Adjustment and Appeals

- Little Rock Planning Commission

- MacArthur Military History Museum Commission

- Midtown Redevelopment District No. 1 Advisory Board

- Oakland Fraternal Cemetery Board

- Parks and Recreation Commission

- Port Authority

- Project Progress Committee

- Racial and Cultural Diversity Commission

- River Market District Design Review Committee

- Sanitary Sewer Committee

- Sister Cities Commission

- Zoo Board of Governors

Other Offices

- Little Rock Mayor's Office

- Little Rock Vice Mayor's Office

- Little Rock City Manager's Office

- Little Rock Board of Directors

- Little Rock City Clerk's Office

Demographics, Economics, Transportation

Demographics

Little Rock is the capitol city of the State of Arkansas. The city encompasses 122 square miles of incorporated land. In 2003 the U.S. Census Bureau estimated population of the city was 184,053, with 55.1% Caucasian, 40.4% African American, and 2.7% Hispanic. More than half a million people live in the Greater Little Rock Metropolitan area.

Population:

- 1820 - 13 (est.)

- 1830 - 430 (est.)

- 1833 - 665 (special census)

- 1836 - 726 (special census before Arkansas statehood)

- 1840 - 1,531

- 1850 - 2,167

- 1860 - 3,727

- 1870 - 12,380

- 1880 - 13,138

- 1890 - 25,874

- 1900 - 38,307

- 1910 - 45,941

- 1920 - 65,142

- 1930 - 81,679

- 1940 - 88,039

- 1950 - 102,213

- 1960 - 107,813

- 1970 - 132,483

- 1980 - 159,024

- 1990 - 175,795

- 2000 - 183,133

- 2007 - 193,275 (est.)

Economy

Transportation

The city is known for six important downtown bridges over the Arkansas River connecting the city to North Little Rock and northern Pulaski County. The six bridges are the Baring Cross Bridge, Broadway Bridge, Main Street Bridge, Junction Bridge, I-30 Bridge, and the Rock Island Bridge. Other bridges in the city that connect the north and south banks of the river are the I-430 Bridge, the pedestrian-only Big Dam Bridge, and the I-440 Bridge.

The city lies at the intersection of two major interstates, I-30 and I-40. East-west crosstown traffic is facilitated by I-630. The city is ringed on the west by I-430 and on the east by I-440. Interstate 530 connects the city to Pine Bluff to the south. Two other limited access highways are U.S. Highway 67, connecting Little Rock to Jacksonville to the northeast, and Arkansas Highway 100, connecting the city to Maumelle to the northwest.

Arkansas Highway 10 in the city is known as Cantrell Road. Arkansas Highway 5 follows Stagecoach Road and Colonel Glenn Road. U.S. Highway 67 and U.S. Highway 70 are merged with I-30 on the southwest and northern sides of the city, both following University Avenue, Asher Avenue, Roosevelt Road, and Broadway downtown. Arkansas Highway 300 follows Colonel Glenn Road into western Pulaski County. Access to the city from Sweet Home and the southeast is possible on Arkansas Highway 365. In southwestern Little Rock Arkansas Highway 338 is known as Baseline Road. Arkansas Highway 367 is known as Pike Street.

Little Rock is served by several railroads. The Union Pacific Railroad enters downtown by way of two separate lines entering the city from the northeast, northwest, southeast, and southwest. Amtrak uses the northeast-to-southwest line for passenger traffic, stopping at Union Station near the Arkansas State Capitol. The Little Rock and Western Railway follows the Arkansas River downtown from the direction of Bigelow in Perry County.

Passenger travel is also facilitated by the Little Rock National Airport.

History of Little Rock

Human prehistory

The Woodland period Plum Bayou people settled in this part of the Arkansas River valley around 650 AD. The original name of the inhabitants is unknown; the name Plum Bayou is derived from a nearby creek. Remains from this culture are still visible at the Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park sixteen miles southeast of the city near Scott. The Plum Bayou culture occupied the Toltec Mounds site until 1050 AD, when they were abandoned.

The Quapaw (Ugahxpa, or "Downstream People") are a Native American tribe that may have migrated from the Ohio River Valley to the Lower Mississippi and Arkansas River valleys before the time of European settlement. Other native peoples referred to the Quapaw as the "Akansea," from which the name of the state of Arkansas is derived.

European discovery and exploration

The site of the present city of Little Rock was first visited by European explorers in 1722, when Frenchman Jean-Baptise Bénard de la Harpe made note of La Petite Roche ("the little rock"). The first squatter on Little Rock land may have been William Lewis, who built a shelter at the present location of the Old State House in 1812.

A Crossroads Settlement

On August 24, 1818, the Quapaw Indians ceded all their lands west of present Rock Street in Little Rock to the United States in preparation for a move of the seat of government to the city from Arkansas Post near the mouth of the Arkansas River. The loss of land amounted to 16 million acres in southern and western Arkansas, including almost all land held between the Arkansas and Red rivers. That same year Pulaski County became part of the Missouri Territory. The city gained a post office on April 10, 1820, with the appointment of postmaster Amos Wheeler, and became the territorial capitol on October 24, 1820. Little Rock was surveyed in 1821, and briefly became known as "Arkopolis." The first Little Rock school opened under Jesse Brown in 1823.

On November 15, 1824, the Quapaw tribe ceded the remainder of their lands east of Rock Street, an amount totaling 1.5 million acres. A Quapaw Line monument dedicated to the memory of these two treaties stands today on the southeast corner of Commerce and Ninth streets.

Little Rock as State Capitol

The Arkansas legislature incorporated incorporated Little Rock as a town on November 7, 1831, and as a city on November 2, 1835. It became the state capitol in 1836. The first steam ferry across the Arkansas River began operations on June 27, 1839, and the first hotel - Anthony House - opened in 1841. By 1850 the city, expanding rapidly during the cotton boom, held about 2,000 denizens. The population grew to 3,727 in 1860. By 1870 the number of residents had tripled to 12,380.

Civil War Little Rock

During the American Civil War the city observed much military activity. On February 8, 1861, the Federal Little Rock Arsenal was attacked by Confederate forces and its store of ammunition, cannon, and other weapons seized. Under the leadership of Major General Samuel R. Curtis 22,000 Union soldiers feigned an attack on Little Rock in May 1862, causing the state to establish a government in exile in Jackson, Mississippi.

The city was captured in September 1863 by fourteen thousand federal troops under the command of Major General Frederick Steele. C.S.A. Major General Sterling Price attempted to defend the city with eight thousand men and miscellaneous cavalry. Steele bypassed this installations by crossing the Arkansas River on a pontoon bridge erected at Terry's Ferry. Confederate cavalrymen under the leadership of Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke met Union cavalry under Brigadier General John W. Davidson at Fourche Bayou east of the city (site of the present Port of Little Rock). The Confederate stand at Fourche Bayou gave Price time to evacuate all of his troops before the city surrendered for the duration of the war.

A City of Roses

At the turn of the century Little Rock was called the "City of Roses," for its long tradition of civic gardening. In 1914 the Arkansas State Capitol was completed in midtown Little Rock, precipitating a building boom that culminated with the completion of the fourteen-story Donaghey Building in 1926. Downtown retail development, spurred by flagship stores Blass Department Store and M. M. Cohn, grew until 1957 when the first suburban shopping center (Village Shopping Center) opened its doors at the corner of Asher & University.

The Great Depression

The Second World War

The Crisis of 1957

Little Rock had long been controlled by the mayor-alderman form of government. On November 11, 1957, voters turned control over to a city manager. Local historian James Bell has suggested that the change was made in part because of the turmoil roiling the city during the Little Rock Crisis: "Possibly because of state intervention in the Little Rock school crisis, which in turn caused Federal intervention, the city's voters favored a stronger municipal government."

Revitalization Efforts

The City of Little Rock has taken a number of steps since the 1960s to restore downtown to its former position of prominence and hospitality. The city has focused on some of the same goals driving other revitalizing cities like Portland, San Antonio, and Baltimore. These goals include improving the quality and number of downtown entertainment venues and attractions, adding green space buffers, beautiful streetscapes, and waterfront attractions, improving walkability and transportation options, creating safe living spaces for a twenty-four hour resident population, revisiting zoning laws, and not least of all forging significant public-private partnerships and cooperative ventures.

A number of government and public-private partnerships have been formed over the years to accomplish these aims, most notably the Little Rock Housing Authority (1937), Urban Progress Association (1959), Downtown Little Rock Unlimited (1959), Little Rock Unlimited Progress (1970), the Metrocentre Improvement District (1973), and the Little Rock Downtown Partnership (1985).

Redirecting attention back downtown has not been easy. In an attempt to recapture some of the trade draining into the western suburbs the group Little Rock Unlimited Progress inaugurated the ill-fated $4.5 million Metrocentre Mall which replaced Main Street from Third Street to Seventh Street with a brick-lined pedestrian mall in 1975. More successfully in 1982 the Statehouse Convention Center opened near the corner of Main and Markham next to the new Excelsior Hotel. The shuttered Capital Hotel reopened after $10 million in renovations the very next year. Also in 1983 the Little Rock Department of Parks and Recreation opened the $2 million Riverfront Park, an idea on the drawing board since 1914, and kicked off the inaugural Memorial Day weekend event known as Riverfest. By 1988 the city hosted 600 conventions and 220,000 visitors due in no small part to the efforts of downtown city leaders.

The apparent success of Metrocentre Mall encouraged investors to sink $13 million into city revenue bonds to fund the Main Street Market project, which brought an enclosed shopping center to the downtown district in 1987. Five buildings were connected along Capitol and Main streets to form an indoor mall. The oldest escalators in the state, once owned by JCPenney, were refurbished as well as 177,000 square feet of office, restaurant, and retail space. Main Street Market was connected to the Arkansas Repertory Theatre and a parking deck by skywalks. Within four years, however, the Market failed as a retailing and entertainment destination. Today it is exclusively used as office space. Metrocentre Mall failed as well. Main reopened to vehicular traffic around 1995. Barry Travis, former executive director of the Little Rock Convention and Visitors Bureau, has blamed a lack of free parking as a major reason for the decline of both revitalization efforts. The 1994 HBO documentary Gang War: Bangin' in Little Rock also reinforced the public imagination of downtown as an unsafe destination. Much of the east side was composed of aging or derelict warehouses.

A "critical mass" may only have been reached in 1996 when Ottenheimer Market Hall reopened in the River Market District to great fanfare. The Market Hall almost immediately helped renew retail opportunities and bring nightlife back into the city center. By 2001 the city was hosting 700 conventions and 300,000 visitors who spent an estimated $100 million. A five-year effort to site the William J. Clinton Presidential Center in the city was capped by the 2004 dedication of the Clinton Library, bringing an estimated $1 billion in additional investment into the historic River Market District.

Little Rock Today

Attractions:

- Arkansas Arts Center

- Museum Center/Arkansas Museum of Discovery

- Witt Stephens Jr. Central Arkansas Nature Center

- Historic Arkansas Museum

- Old State House

- Robinson Center

- La Petite Roche

- MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History

- Murphy Keller Education Center

- Riverfest Amphitheater

- Sculpture Promenade

Amenities:

- Restaurants and Music (Andina Café and Coffee Roastery, Ashley's, Boscos, Boulevard Bread Company, Café 42, Capital Bar and Grill, Capriccio Grill Italian Steakhouse, Flying Fish, Flying Saucer, Sonny Williams' Steak Room, Sticky Fingerz, Willy D's Piano Bar)

- River Market Farmer's Market

- Hotels (Peabody Hotel, Capital Hotel, Comfort Inn & Suites Downtown, Courtyard-Little Rock Downtown, Doubletree-Little Rock, Holiday Inn Presidential Conference Center)

- Condominiums (300 Third Tower, Arkansas Capital Commerce Center, Block 2 Lofts, First Security Center, Residences at Building 5, River Market Tower, Rock Street Lofts, Tuf-Nut Lofts)

Events:

- Riverfest

- Little Rock Marathon

- Downtown Thursdays (1994)

- Arkansas Flower and Garden Show

- Arkansas Literary Festival

- Arkansas Sculpture Invitational

- CARTI Tour de Rock

- Cruisin' in the Rock

- Little Rock Film Festival

- Movies in the Park

- Territorial Fair

Organizations:

- Downtown Little Rock Partnership

- Nonprofits (Clinton Foundation, Heifer International, Audubon Arkansas)

- Greater Little Rock Chamber of Commerce

- Fifty for the Future

- Downtown Navigator Program

- Historic District Commission

- Quapaw Quarter Association

Public Services:

- Little Rock Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Department of Parks and Recreation (Riverfront Park)

- Central Arkansas Library System (Main Library, Arkansas Studies Institute, Cox Creative Center)

- Metrocentre Improvement District

- Clinton School of Public Service

- Pulaski Empowerment Zone

Transportation and Trails:

- Metroplan

- Millennium Trail

- Little Rock River Rail

- Union Station

- Junction Bridge

- Rock Island Railway Bridge

Downtown Headquarters:

- Acxiom River Market Tower

- Candy Bouquet International

- Metropolitan National Bank Tower

- Stephens Inc.

- Stone Ward

References

- David W. Baird, The Quapaw Indians: A History of the Downstream People, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980).

- S. Charles Bolton, "Under Three Flags," in A Documentary History of Arkansas, eds. C. Fred Williams, et al. (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1984), p. 3-5.

- Isaac Joslin Cox, ed., The Journeys of René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, vol. 1 (New York: Allerton Book Company, 1922).

- Jay Harrod and Kerry Kraus, "Capital Improvements: A Look at Little Rock's Past and Future Downtown Revitalization Efforts," Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism, April 9, 2002, unpublished.

- Letha Mills and H. K. Stewart, Greater Little Rock: A Contemporary Portrait (Chatsworth, CA: Windsor Publications, 1990).

- Susan Nichols, Knapp Trail Guide brochure.

- Milton D. Rafferty and John C. Catau, The Ouachita Mountains: A Guide for Fishermen, Hunters, and Travelers (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 10.

- John Hugh Reynolds, ed., "Marquette's Reception by the Quapaws, 1673," Publications of the Arkansas Historical Association 1 (1906): 500-502.

- George B. Rose, "Little Rock: The City of Roses," in Historic Towns of the Southern States, ed. Lyman Pierson Powell (G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1904), 537-556.

- Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park, The Griggs Canoe brochure.

- Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park, Plum Bayou Trail brochure.