American Civil War

During the American Civil War the city of Little Rock, population 3,727 (2,874 white, 853 black), was the site of much military and civilian activity.

Secession

On January 15, 1861, Governor Henry Rector signed a law calling for a secession vote. A convention to consider the matter came together on March 4th in Little Rock. On May 6th a secession ordinance passed by a vote of 69 to 1. Arkansas joined the Confederate States of America on May 18th. Arkansas' U.S. congressional delegation resigned on July 11th. The Arkansas legislature passed a Confederate War tax in a special session on November 4th.

1862

Confederates had attacked the federal Little Rock Arsenal just south of downtown and looted its store of ammunition, cannon, and other weapons on February 8th. Over the next eighteen months the C.S.A. assembled twenty-six day laborers, three gunsmiths, a shop foreman, a clerk, carpenter, and "laboratorian" to begin manufacturing sorely needed cartridges. Paper for making the cartridges was so scarce that the Arkansas State Library was ransacked for spare material. Local foundries were enlisted to make grapeshot, and prisoners in the Arkansas State Penitentiary manufactured such articles as shoes, boots, uniforms, drums, gun carriages, caissons, and wagons.

On May 1, 1862, the legislature passed the "twenty nigger" law, which exempted white planters who owned twenty or more slaves from military service.

Under the leadership of Major General Samuel R. Curtis 22,000 Union soldiers feigned an attack on Little Rock in May, causing the state legislature to disband, and resulting in Governor Rector's establishment of a government in exile in Jackson, Mississippi. Most manufacturing was relocated to more secure Arkadelphia, and later to Texas and Louisiana.

1863

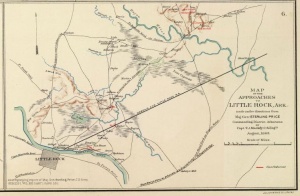

The city was captured in September 1863 by fourteen thousand federal troops under the command of Major General Frederick Steele. C.S.A. Major General Sterling Price attempted to defend the city with eight thousand men and miscellaneous cavalry, which he described as "in excellent condition, full of enthusiasm and eager to meet the enemy." Price erected rifle pits and earthen fortifications two-and-a-half miles downstream from the capital city on the Arkansas River, at Dark Hollow, and along the high ground on the north side of the river opposite downtown Little Rock. Three large cannon were stationed on Big Rock and Park Hill. He also ordered strategic cavalry attacks of the Union Army camp.

Steele bypassed this installations by crossing the Arkansas River on a pontoon bridge erected at Terry's Ferry on September 9th. The crossing was completed the next day. At 11 AM on the 10th Price began evacuating his soldiers from the north side of the River using his own pontoons, and decamped for Arkadelphia. Confederate cavalrymen under the leadership of Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke met Union cavalry under Brigadier General John W. Davidson at Fourche Bayou east of the city (site of the present Port of Little Rock). "Every advantageous foot of ground from this point onward was warmly contested by them," Davidson later reported, "my cavalry dismounting and taking it afoot in the timber and cornfields." The Confederate stand at Fourche Bayou gave Price time to evacuate all of his troops from the city by 5 PM. The capitol surrendered to Steele at 7 PM.

Total casualties among the Confederates in this campaign, called the Battle of Little Rock by the South and the Battle of Bayou Fourche by the North, numbered about sixty-four men. The tally on the Union side was eighteen killed, one hundred and eighteen wounded, and one missing.

Susan Bricelin Fletcher, wife of a Pulaski County plantation owner, wrote of the Federal occupation, "After we were visited by the first half dozen squads of blue coats, we knew what civil war was when it was brought to your door. They first demanded water, then feed, after which they began to look around to see what could be carried away or destroyed. ... They killed the cattle on one occasion. I saw my hillside pasture red with the blood of slain cattle. They tore photographs from the wall, burnt the cotton bales, took our combs and every vestige of food. We would have to send neighbors back to the woods for food, as not a crumb of anything would be left."

After the loss of Little Rock, Governor Harris Flanagin established a new state capitol in Washington, Hempstead County.

1864 and Beyond

Reconstruction

References

- "Arkansas Back to the Union," New York Times, June 3, 1862.

- Tom Dillard, "Arkansas Goes to War," Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 16, 2009.

- "Important from Arkansas; Capture of Fort Smith by General Blunt; Little Rock Evacuated by the Rebels," New York Times, September 11, 1863.

- "Important from Arkansas; Defeat of the Rebel Forces Under Marmaduke and Price," New York Times, September 3, 1863.

- "Occupation of Little Rock, the Capital of Arkansas, by Our Forces," New York Times, June 1, 1862.

- "Official Reports of Gen. Steele's Movements; The Defeat of Marmaduke's Forces," New York Times, September 6, 1863.

- "The Rebels in Arkansas; Kirby Smith and Price Reported at Little Rock, with 40,000 Men," New York Times, September 2, 1863.

- Ira Don Richards, "And in the War Came," in Story of a Rivertown: Little Rock in the Nineteenth Century (1969), 59-79.

- "The War in Arkansas; An Expedition Moving Toward Little Rock," New York Times, August 9, 1863.

- "The War in Arkansas; Gen. Steele's Expedition to Little Rock," New York Times, August 16, 1863.

- "The War in Arkansas; Gen. Steele's Expedition to Little Rock," New York Times, August 24, 1863.

- "The War in Arkansas; The Rebels Evacuating Little Rock," New York Times, September 12, 1863.