Difference between revisions of "Carry Nation"

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

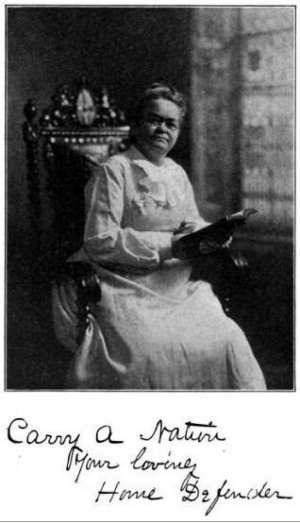

[[Image:Carry-nation.jpg|thumb|300px|Carry Nation.]] | [[Image:Carry-nation.jpg|thumb|300px|Carry Nation.]] | ||

| − | '''Carry A. Nation | + | '''Carry A. Nation''' (1846-1911) was a temperance crusader. She was famous for "smashing" or vandalizing saloons and other places that commonly served alcohol. |

Nation was born Carrie Amelia Moore in 1846 to slave-owning parents in Garrard County, Kentucky. The family had a history of mental illness, and Nation's mother had occasional delusions where she mistook herself for Queen Victoria. Before and during the [[Civil War]] the family lived in western Missouri, particularly Belton and Kansas City. In 1867 she married the alcoholic Union physician Charles Gloyd, who died only two years later. Nation later attributed her temperance calling to the ravages of his disease. Nation built a home in Holden, Missouri, and attended the Normal Institute in nearby Warrensburg to earn her teaching certificate. | Nation was born Carrie Amelia Moore in 1846 to slave-owning parents in Garrard County, Kentucky. The family had a history of mental illness, and Nation's mother had occasional delusions where she mistook herself for Queen Victoria. Before and during the [[Civil War]] the family lived in western Missouri, particularly Belton and Kansas City. In 1867 she married the alcoholic Union physician Charles Gloyd, who died only two years later. Nation later attributed her temperance calling to the ravages of his disease. Nation built a home in Holden, Missouri, and attended the Normal Institute in nearby Warrensburg to earn her teaching certificate. | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

In 1874 she married David A. Nation. The couple bought a cotton plantation ion the San Bernard River in Texas, but failed at farming. They eventually fell to running hotels, while David practiced law. After becoming embroiled in the local Jaybird-Woodpecker War in 1888, the family moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas. David became a preacher and Carry ran a local hotel. Here Carry Nation began working as a temperance advocate, founding a chapter of the [[Woman's Christian Temperance Union]]. In 1899 she had a powerful vision in which a voice exhorted her to "go to Kiowa" and "take something in your hands, and throw at there places in Kiowa and smash them." In Kiowa she destroyed first Dobson's Saloon with "smashers" (rocks) and two others. After smashing bars in Wichita, her husband joked that she might do more damage with hatchets, which led her to take up the tool. Authorities arrested Nation about thirty times between 1900 and 1910 after devastating attacks, which she called "hatchetations," on places serving liquor. | In 1874 she married David A. Nation. The couple bought a cotton plantation ion the San Bernard River in Texas, but failed at farming. They eventually fell to running hotels, while David practiced law. After becoming embroiled in the local Jaybird-Woodpecker War in 1888, the family moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas. David became a preacher and Carry ran a local hotel. Here Carry Nation began working as a temperance advocate, founding a chapter of the [[Woman's Christian Temperance Union]]. In 1899 she had a powerful vision in which a voice exhorted her to "go to Kiowa" and "take something in your hands, and throw at there places in Kiowa and smash them." In Kiowa she destroyed first Dobson's Saloon with "smashers" (rocks) and two others. After smashing bars in Wichita, her husband joked that she might do more damage with hatchets, which led her to take up the tool. Authorities arrested Nation about thirty times between 1900 and 1910 after devastating attacks, which she called "hatchetations," on places serving liquor. | ||

| − | Hatchet Hall at 35 Steele Street in [[Eureka Springs]], Arkansas, served as the home of Carry Nation for two years beginning in 1909. Nation had visited Eureka Springs in 1907 to give temperance speeches and help organize a local temperance group, and her husband had visited the town to take in the healing waters as an arthritis cure. She first purchased a cabin and farm in Alpena Pass, but then felt a calling to purchase Hatchet Hall and other nearby cottages to board widows, abused women and children, and local school girls. The school girls attended a college she created in the neighborhood called the "Carry A. Nation School" or simply "National College." She spoke of it in terms of building an "associative household." | + | [[Hatchet Hall]] at 35 Steele Street in [[Eureka Springs]], Arkansas, served as the home of Carry Nation for two years beginning in 1909. Nation had visited Eureka Springs in 1907 to give temperance speeches and help organize a local temperance group, and her husband had visited the town to take in the healing waters as an arthritis cure. She first purchased a cabin and farm in Alpena Pass, but then felt a calling to purchase Hatchet Hall and other nearby cottages to board widows, abused women and children, and local school girls. The school girls attended a college she created in the neighborhood called the "Carry A. Nation School" or simply "National College." She spoke of it in terms of building an "associative household." She sold water bottles to support her work, and also offered hot and cold water baths to paying guests. She continued to preach temperance, but restricted her efforts to pulling cigars and cigarettes out of the mouths of men she encountered on the sidewalk. |

| − | Nation | + | After Nation suffered a nervous breakdown in December 1910, and died in Leavenworth, Kansas, on June 9, 1911. Hatchet Hall became the residence of Elsie and Louis Freund, both of whom were artists. If not for the Freund's purchase the house would have been destroyed and sold for wood. Hatchet Hall then became the [[Art School of the Ozarks]] from 1940 to 1951, where the Freunds would teach art classes in the summer. After the Freunds left Hatchet Hall, it became a museum to both Nation's life and her passion – temperance. Currently, the house is a landmark but remains inaccessible to the public. |

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | + | *Fran Grace, ''Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life'' (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 262-277. | |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[http://www.kshs.org/p/online-exhibits-carry-a-nation-introduction/10588 Kansas Historical Society - Online Exhibits - Carry A. Nation, Introduction] | ||

[[Category:1846 births]] | [[Category:1846 births]] | ||

[[Category:1911 deaths]] | [[Category:1911 deaths]] | ||

[[Category:Alcohol]] | [[Category:Alcohol]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:58, 14 May 2011

Carry A. Nation (1846-1911) was a temperance crusader. She was famous for "smashing" or vandalizing saloons and other places that commonly served alcohol.

Nation was born Carrie Amelia Moore in 1846 to slave-owning parents in Garrard County, Kentucky. The family had a history of mental illness, and Nation's mother had occasional delusions where she mistook herself for Queen Victoria. Before and during the Civil War the family lived in western Missouri, particularly Belton and Kansas City. In 1867 she married the alcoholic Union physician Charles Gloyd, who died only two years later. Nation later attributed her temperance calling to the ravages of his disease. Nation built a home in Holden, Missouri, and attended the Normal Institute in nearby Warrensburg to earn her teaching certificate.

In 1874 she married David A. Nation. The couple bought a cotton plantation ion the San Bernard River in Texas, but failed at farming. They eventually fell to running hotels, while David practiced law. After becoming embroiled in the local Jaybird-Woodpecker War in 1888, the family moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas. David became a preacher and Carry ran a local hotel. Here Carry Nation began working as a temperance advocate, founding a chapter of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. In 1899 she had a powerful vision in which a voice exhorted her to "go to Kiowa" and "take something in your hands, and throw at there places in Kiowa and smash them." In Kiowa she destroyed first Dobson's Saloon with "smashers" (rocks) and two others. After smashing bars in Wichita, her husband joked that she might do more damage with hatchets, which led her to take up the tool. Authorities arrested Nation about thirty times between 1900 and 1910 after devastating attacks, which she called "hatchetations," on places serving liquor.

Hatchet Hall at 35 Steele Street in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, served as the home of Carry Nation for two years beginning in 1909. Nation had visited Eureka Springs in 1907 to give temperance speeches and help organize a local temperance group, and her husband had visited the town to take in the healing waters as an arthritis cure. She first purchased a cabin and farm in Alpena Pass, but then felt a calling to purchase Hatchet Hall and other nearby cottages to board widows, abused women and children, and local school girls. The school girls attended a college she created in the neighborhood called the "Carry A. Nation School" or simply "National College." She spoke of it in terms of building an "associative household." She sold water bottles to support her work, and also offered hot and cold water baths to paying guests. She continued to preach temperance, but restricted her efforts to pulling cigars and cigarettes out of the mouths of men she encountered on the sidewalk.

After Nation suffered a nervous breakdown in December 1910, and died in Leavenworth, Kansas, on June 9, 1911. Hatchet Hall became the residence of Elsie and Louis Freund, both of whom were artists. If not for the Freund's purchase the house would have been destroyed and sold for wood. Hatchet Hall then became the Art School of the Ozarks from 1940 to 1951, where the Freunds would teach art classes in the summer. After the Freunds left Hatchet Hall, it became a museum to both Nation's life and her passion – temperance. Currently, the house is a landmark but remains inaccessible to the public.

References

- Fran Grace, Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 262-277.